The General

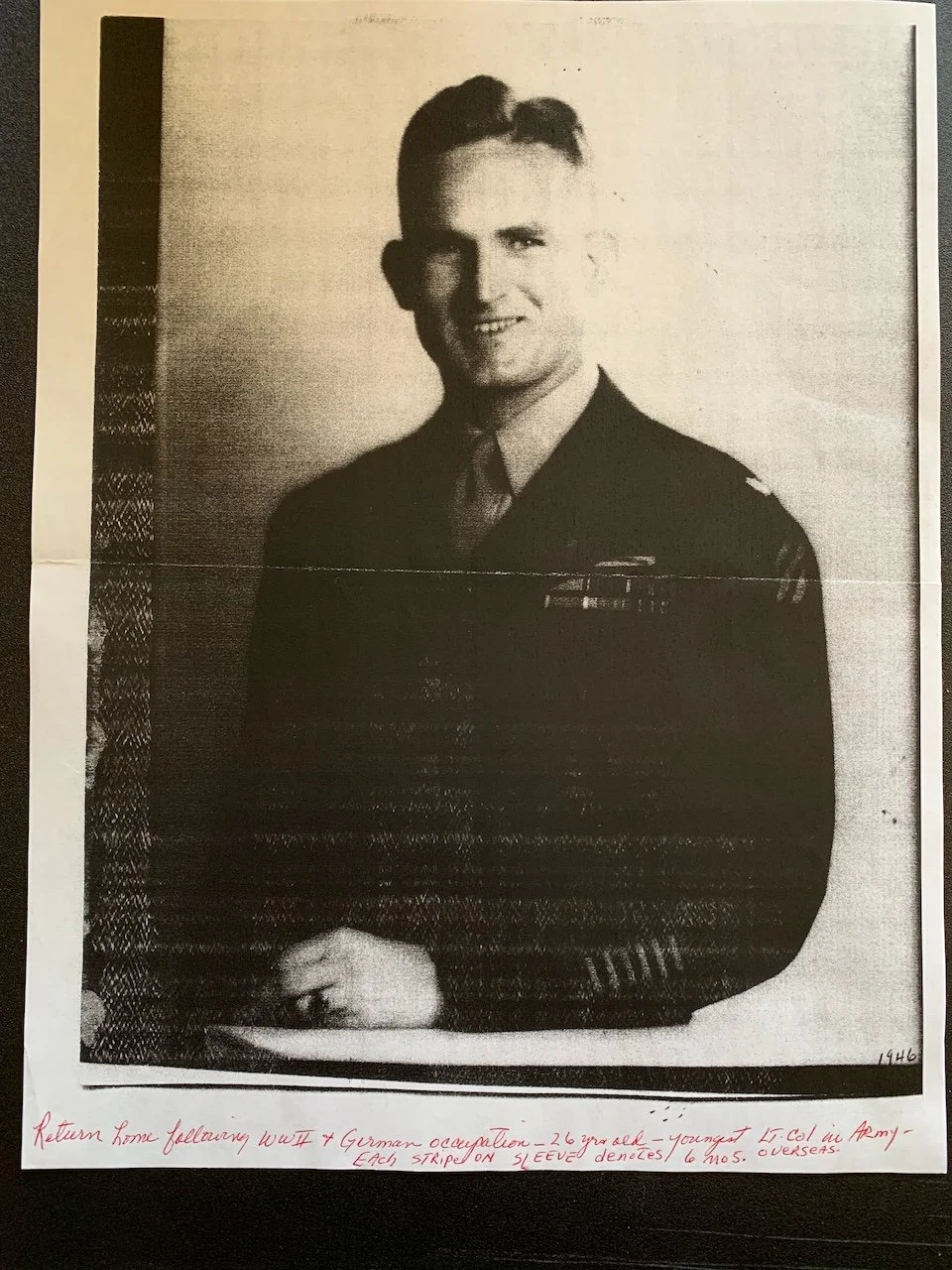

The General

Written By: Nicholas Pascarella

When I was young, my grandfather, whom I affectionately called Grandaddy Bill, would hide my toys and stuffed animals in plain sight. On the tops of picture frames, sitting on stacks of wood beside the fireplace, nestled into couch pillows; I’d usually end up aghast and demand he reveal their location to me. With that wry, barely-there smile of his, he’d shrug and ask what I was talking about. The ends of his mouth always turned down, but his cheeks would raise ever so slightly, drawing the inward part of his lips into the smallest hint of a smile, and I would know he was telling me outright lies.

At his house in Roanoke, VA, with my grandmother, Bertha Mitchell Rosson, or Yaya (Greek for grandmother), my siblings, cousins and I would run around with toy guns and footballs in his basement lair while the adults discussed adult things upstairs. His Doughboy award and a framed photo of him as a two star Major General greeted us as we raced down the stairs and across the landing. Above his mantle hung a generously sized print of him riding a captured NVA bicycle in Vietnam. A hollowed out elephant's foot held his umbrellas. Eastern Fu Dogs guarded his neatly tended desk. Among his library were scattered photos of him meeting with dignitaries or other high-profile leaders in military and politics, at home and abroad.

He never spoke about his service. I regretfully never asked. He was much too interested to hear me play guitar or hear my sister sing. Even his uniform was donated to the Army War College. The storage portion of his basement was lined wall-to-wall with an incredible amount of dusty items collected from around the world. His grip, even in old age, was steel. To shake his hand was to feel your own hand bones crunch.

When he passed, Yaya began receiving communications from across the globe. She had trouble keeping track of everything as the volume of the mail quickly overwhelmed her. Things we never knew came to light, filling in the many gaps on Grandaddy's life that we had little knowledge of. Many years later, there were still people that wrote to Yaya about Grandaddy. I was able to copy many of the documents, letters, photos, tattered newspaper clippings and incomplete records, and began to paint a timeline with the vibrant color and intensity of the life of General Rosson, my Grandaddy Bill.

Some things I already knew. He was a master parachutist in the Army. He served four tours in Vietnam. 10 in WWII. He played golf with Colin Powell and President Eisenhower in the same lifetime. I knew he attended Oregon University, but the details were hazy. Some of the first few clippings filled in the first part of that story, and I followed the trail he weaved through journalist's eyes in the plethora of yellowed documents and aged photos, piecing together a picture that connected the big events of his life. I am pleased and honored to introduce to you General William Bradford Rosson.

He was born in Des Moines, Iowa on August, 25, 1918. His father was a University of Oregon law professor, and the family moved back to Eugene, Oregon early on. Impressed by inspiring Army legends regaled to him by his Boy Scout instructor, a former Army sergeant himself, he twice applied to West Point, but could not get an appointment from his Congressman. Instead, he enrolled in the R.O.T.C. at the University of Oregon, and paid his way through college by tending furnaces, doing odd jobs and working at a cannery.

He graduated Oregon University in 1940 on the honor roll with straight A's, and was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in the US Army as the Nazi war machine blitzkrieg'd its way across Europe. He was assigned to the 15th Infantry at Ft. Lewis, and was quickly made platoon leader of E Company. A month later he was transferred from the 15th to the 7th (or as it was known, the Cotton Baler Regiment) and quickly made platoon leader once more. He joined Second Battalion HQ, 7th Infantry as the Detachment Commander and also the Transportation Officer.

Previewing the North African invasion on the beach of San Diego Bay, he helped plan and engineer the landings. This training was invaluable in forming the groundwork for the massive invasions to come. He was made S-3 of the 7th Regiment, 3rd Infantry (or the "Rock of the Marne" based on the group's WWI exploits), a position he held for the duration of the division's time in the US, and was the position he held when they were shipped across the Atlantic for battle.

The 3rd Infantry Division went ashore during "Operation Torch", the American invasion of North Africa. His regiment landed at Fedala, Morocco, under fire raining down from Vichy French aircraft and shore batteries. "It was a good indoctrination to say the least," Rosson said. They fought their way across North Africa against Hitler's "Desert Fox", Nazi General Edwin Rommel and his Afrika Korps. They continued battling through Sicily as the war ground on and American involvement increased.

Just prior to the invasion of Nazi-occupied Anzio, Italy, he assumed command of the Third Battalion, Seventh Infantry. He went ashore on the corpse-strewn beaches of Anzio, a scene bloodier than the Normandy beaches of D-Day, and during this time was faced with some of the most vicious, close-quarters fighting of the war. One situation saw three heavily armed and reinforced German Divisions squaring off against a surrounded and beleaguered 3rd Infantry. May 23, 1944, the 3rd Division suffered 995 casualties, believed to be the single highest total for any division in any US war in a single day.

A few months earlier when the Allies had broken out from the beachhead and battles raged inland, he had once again distinguished himself in a surprise night attack on a German-held fortified road junction just outside the town of Cisterna. His thin battalion of 900 men were scattered due to raking fire from a much heavier enemy force. What follows is an excerpt of his Distinguished Service Cross citation:

"...For extraordinary heroism in action, on 31 January 1944, near Cisterna di Littoria, Italy...Lieutenant Colonel ROSSON led his battalion in an advance to take a road junction and a hill, to secure the right flank of his regiment during an attack. Early in the attack one of his assault companies was halted temporarily by severe machine gun and rifle fire. While several enemy riflemen shot directly at him, Lieutenant Colonel ROSSON ran forward to a position within seventy-five yards of the enemy. Exposing himself to intense machine gun fire which barely missed him, he reorganized the two fore-most assaulting platoons and directed their firepower so effectively that the enemy was routed completely. Advancing two thousand yards closer to the objective, one of the assault companies was ambushed by a large enemy force. Moving forward amid tracer bullets which struck the ground at his feet, Lieutenant Colonel ROSSON made a reconnaissance within one hundred yards of the enemy. Deciding the fire-power of one company to be insufficient, he ran three hundred yards to the other assault company, assumed command, and directed a coordinated attack which successfully flanked and routed the enemy. As his battalion reached its objective after an advance of three thousand yards, one of the assault companies became illuminated in the glare of a burning half-track. Three enemy tanks opened fire on the company with cannon and machine guns, inflicting heavy casualties. Hurrying to the company to lead the assault, Lieutenant Colonel ROSSON was subjected to heavy shell fire, shells bursting within ten to twenty-five yards of him. His vision impaired by concussion, his field jacket ripped and his canteen punctured by fragmentation, Lieutenant Colonel ROSSON reorganized the company and figorously pressed the attack to force an enemy withdrawal, which allowed his battalion to reach its objective without further opposition."

Aside from the DSC, he earned (among many, many other awards) the Bronze Star, Legion of Merit, and Purple Heart. When asked about his DSC, he credited his battalion.

On one occasion talking to a reporter later in life, he fondly recalled a meeting with General Omar Bradley during this time period in Italy. Rosson had just delivered a briefing on the front lines, and General Bradley "put his arm around me and patted me on the back. I can still feel that pat today," he said.

Under General Truscott, he was called back to VI Corps as Ass't G-3. He was sent by General John D. "Iron Mike" O'Daniel (Third Division commander) over Rome in a Piper Cub to "look things over" during the battle, and the aircraft barely staggered back to base, shot to pieces around them in thick flack. He was awarded an Air Medal. In an undated news clipping, a reporter asked him to describe the episode that won him the Air Medal and he snapped off the question with: "For flying."

After breaking through at Cisterna and the capture of Rome, he returned to Naples to begin planning for the Normandy invasion. On D-Day, he came ashore in the wake of the 45th Division, rejoining the 3rd Infantry Division at the banks of the Muerthe River. He used what he'd learned from his most inspiring commanders; "Iron Mike" and General Lucian Truscott, and fought through the heavy combat in the Vosges Mountains in France, as the 3rd Division thrust into the Rhine Valley on its push to Munich. He was made Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3, and held this position until war's end.

The waning months of the war were memorable for him, but not for the fighting. In 1999, a newspaper reporter from Extra asked him of his strongest memory from the service, and he pulled up a scene from 1945:

"The liberation of Dachau...And what I saw there was so shocking that I realized that I was witnessing one of the darkest chapters of history, to see the cruelty, the depravity of the treatment of those inmates.

"Here were all these shaven-headed, emaciated people, mostly without shoes in that bitter cold weather, wearing those black-and-white striped uniforms. And they were just delirious that they'd been liberated.

"[In the ovens] you could see the bones burning up in there. Bodies were stacked 15 feet high at one end.

"If we had known... the war would've been different. We'd have had a better sense of what we were fighting for."

He remained on German soil, commanding the 30th Infantry Regiment during the occupation after the war. During this time, "...Bill commanded an area that was next to the Russian Zone. There was a railroad in the American zone that had to go through a small distance in the Russian Zone. The russians would hold up our supply trains to harass the Americans. The 3rd Infantry Division was given the mission of trading some land so the railroad would be in the American Zone. As the G-3, I was the staff officer to assist the Commanding General in negotiating the agreement. Bill was the commander that would enforce the agreement. We found that the Russians wanted something in our area and, in a few weeks, we were able to negotiate an agreement. The commanding General told Bill to work with the Russians and occupy the land as soon as possible, and to remove his troops from the land going to the russians. Bill, working with the Russians, moved his troops into the area very quickly and the Russians moved out. A short time later, the Russians tried to break the agreement. Bill had done such an outstanding job of occupying the area that the Russians could not move back in without a battle. The State Department told me this was the only agreement made with the Russians that was not broken. Bill and my signatures are on the map, with the Russians, that is a part of the agreement." (Major General Lloyd B. Ramsey, USA, Ret.)

Officers who served with him noted his work ethic and drive. "He swarms all over a subject until he's mastered it. He goes out in the field with his men for 72 hours at a stretch in the snow and rain. He's the type who'll get up at 4:30 in the morning when the cooks are brewing up, just to look into things. He never moves until he has a firm grasp of a situation--but he gets that grasp mighty fast," one officer elaborated.

In 1946, he began what was to be three years at the Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, as an instructor. He followed that on with duty serving in the Joint War Plans Branch of the Army General Staff in Washington, D.C.

Instead of going to Korea, he returned to Europe in 1951 to serve on Eisenhower's staff, working in the Plans, Policy and Operations Division of Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) in Paris, France, and was one of three American officers overseeing the formation of NATO. "I saw a great deal of Eisenhower in the early days of SHAPE," a newspaper quoted him saying, "I briefed him on occasion and I played golf with him."

During one such occasion, he remarked "I drove my ball out of bounds, and General Eisenhower gave me a new ball, and I promptly knocked that one out of bounds also. He did not give me a second ball." He mused about another embarrassing situation to the same reporter, this time at a state dinner given by French President Vincent Auriol, when General Rosson and a friend were the last to go through the buffet. He was headed for his seat when his delicate china plate broke in half, plastering the front half of his trousers with French cuisine. "It was a horrible mess," he said, and upon returning to the buffet, he put "a lot less" food on the next plate.

Despite a few rather embarrassing moments, the respect for him among both his soldiers, officers and politicians only grew. At one point while serving in Europe under Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery, Rosson's dry humor, eye for detail, and disdain for self aggrandizement came together in spectacular fashion. According to a story that made the rounds at NATO headquarters, Montgomery entered a meeting (late, leaving everyone waiting) and proceeded to ask each officer in the room, in turn, how many ribbons each had earned. Rosson, having no idea how many awards he had (it was in the 50s at the time) but noting that Montgomery was wearing all 38 of his, flatly stated "Thirty-nine." Montgomery left the room in a huff, and Rosson's popularity with British staff officers soared.

Back and forth across the Atlantic he went, until Lieutenant General O'Daniel was named the head of the US Military Advisory Group in Indo-China in 1954, and he grabbed (then) Colonel Rosson from the Army War College at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. He was assigned a "Special Warfare" position to get acquainted with the Communist "unconventional" type of warfare he was charged to study.

He ended up flying over the major hot spots during the height of the French-Viet Minh struggle, the same location the first Americans were killed shortly after. His own helicopter limped back having been shot to hell over Dien Bien Phu on one particular sortie, and he was notified that he would be awarded the Silver Star. He asked if everyone onboard would receive it, and was informed that since he was the ranking officer, only he would receive it. He declined the Silver Star.

A full article in Pageant, August 1962, includes portions of an interview with General Rosson and a general synopsis of his new position, describing the areas in Indochina of primary concern, notably, where the French were fighting Red guerrillas. When the French bastion fell at Dien Bien Phu, he was given the "staggering job of evacuating 800,000 refugees from Red-held North Vietnam to the South" the article states, before declaring that "working smoothly with French and Vietnamese officials, Rosson completed the job." It should be noted that he was fluent in French, and conducted this entire interview in French.

In 1956, he began a three year assignment with the Joint Chiefs of Staff, serving as the Army member of the Chairman's Staff Group. In this capacity, General Rosson would brief the President, the Secretary of Defense, and Congressional Committees. He graduated from the National War College in 1960, returning to Germany as Assistant Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations, or USAREUR, followed by a role as Assistant Division Commander and Airborne Brigade Commander, 8th Infantry Division.

The Pageant article picks up here: "An infantry squad of 12 enlisted men awoke one morning to find a brigadier general at their elbows. To the amazement of the GIs, Rosson hiked with them, ate with them, ran with them, bivouacked with them." The article quotes a "crusty Special Forces colonel" in Germany at the time: "This was no cheap, morale-building trick. Bill wanted to see what was right and what was wrong with the division. He lived with that squad for days. Then he went to live with a platoon, then a company, right up the ladder. This is the man; this is the way he operates." Following that, his story took an even more interesting turn.

In February, 1962, President John F. Kennedy was already seeing the number of US Special Forces troops grow under his direct order. He had told the generals at the Pentagon the wars of the 60's would not be fought with the lightning and thunder of A-bombs and rockets, but with the stealth and silence of guerrillas. He asked the generals if the nation was prepared to smother communist-inspired and supported "liberation wars" in underdeveloped nations, before fervently declaring that no, the nation was not prepared. He would see to it that the US develop a deep well of experienced Special Forces units.

The Army called General Rosson back to D.C. to serve as Special Assistant to the Chief of Staff, US Army, for Special Warfare (or 'guerrilla warfare'), and as Assistant Deputy Chief of Staff for Military Operations. In this latter capacity, he represented the US Army on the US Section of the Inter-American Defense Board. As the youngest general in Army history at 43 years old, he was put in charge of the program for training anti-guerilla fighters. The aim wasn't just to make better soldiers, but to make teachers to combat hunger, disease, poverty and ignorance; the "Four Horsemen" who ride at the head of Communist guerrilla bands in every "war of liberation."

In the article (Pageant, August 1962), the interviewer asks General Rosson about that aim, and he responded: "In the Special Forces, we have medics who can teach soldiers and civilians how to treat disease, improve sanitation, build hospitals. We have demolition men who can build roads, radio men who can bring electric lights to farms, weapons men who can teach the construction of machinery. One small Special Forces unit can teach children and adults everything from reading and writing to surgery."

He continued, "If we can take the hunger pains out of a villager's belly, we have taken away one more soldier from a Red guerrilla band, one more source of food for a Red guerrilla leader, one more home for a Red guerrilla to hide in." The article described his office at the pentagon like a vault. Rosson continued in a "low, steady voice" after puffing on a cigar, "...our soldiers must teach troops how to go into mountains, swamps, jungles, or deserts---and stay there. Like the guerrillas, these troops must learn to live off the land, fight with makeshift weapons, and--most important--make friends with the civilian population. This is the heart of the matter. From our own experience and the writings of guerrilla leaders like Mao Tse-tung, we know that the guerrilla cannot live without the help of the people."

He became known as the Guerrilla General.

He stood for his men, stating to a reporter that the way his men were being used was a "waste of manpower" in mid 1962.

One officer in the pentagon said: "I can tell you this: he isn't a gung-ho type who'll charge around Washington waving the flag for Special Forces. He'll think, he'll plan, and he'll integrate this operation tightly with the rest of the Army. And he'll quickly weed out the weak reeds, and push ahead the good men. He'll give it aggressive leadership, but it'll be intelligent leadership. Bill Rosson is just a damn brilliant man and a superb Army officer."

General Rosson was selected as the next Director of the US Strike Command Joint Test and Evaluation Task Force, primarily testing and evaluating Army and Air Force air mobility concepts, serving at that position until 1965.

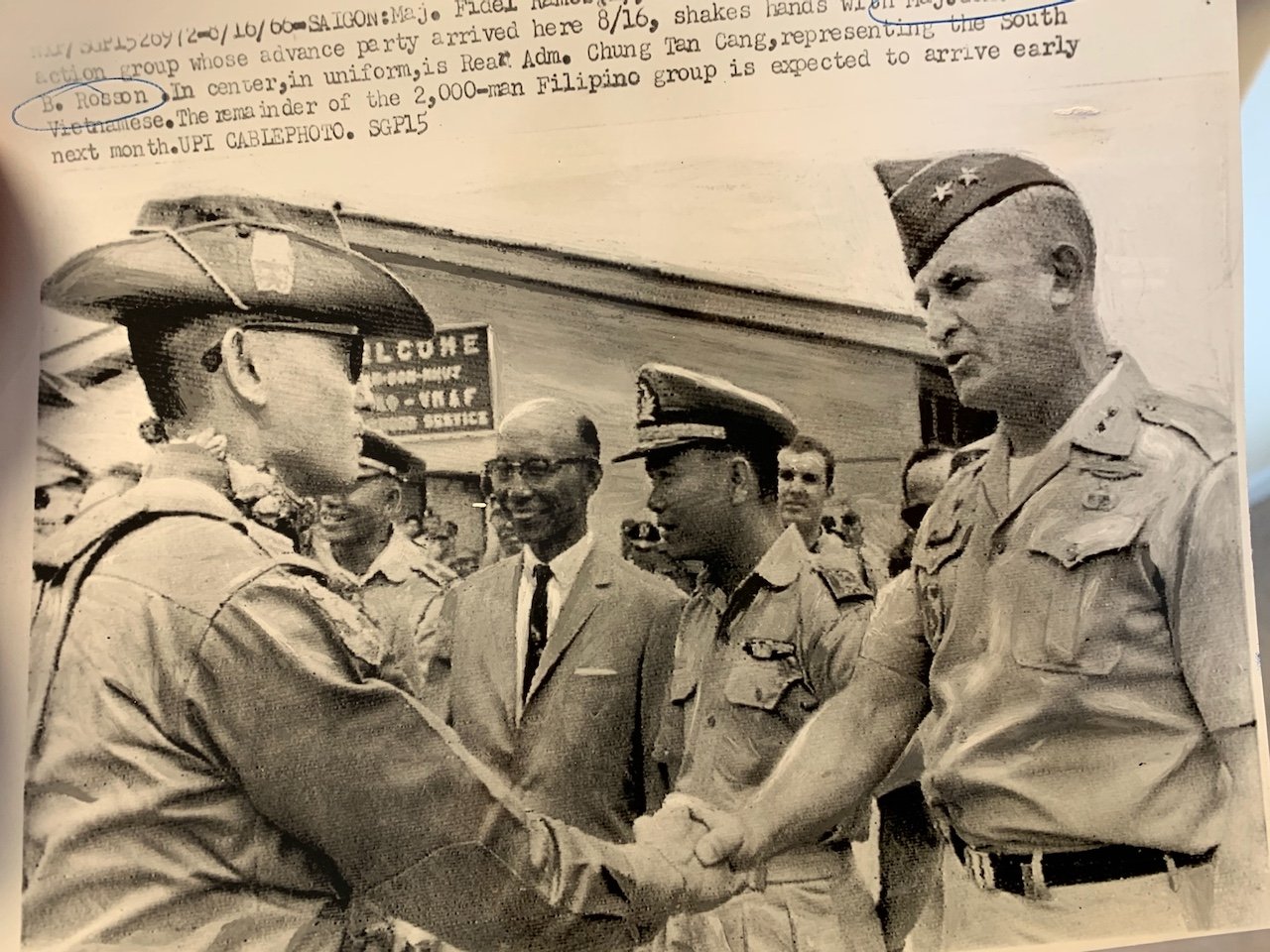

He was assigned Chief of Staff, US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, in April 1967. He was placed in command of Task Force Oregon, operating in the I CTZ, Republic of Vietnam. That information gave me pause. During the Vietnam War, that was not traditionally Army territory. I came across a newspaper clipping of a then Lt. General W. B. Rosson inspecting a shirtless soldier, the photo caption describing a firebase on a hilltop in Dak To in the Central Highlands in Vietnam while he was commanding I Corps. I had to read it twice before it sunk in. You read that correctly, I Corps. The Marines.

On July 31, 1967, he was named Commanding General, I Field Force, Vietnam. His driver from that time wrote a book on his Vietnam experiences, and told a story from the Tet Offensive in early 1968; General Rosson decided to visit the ARVN South Vietnamese Command post at Bam Me Thuot. This area seemed to always be in the thick of battle, and this meeting was a few days after the start of Tet. They did not know before they took off, but the base expected to be overrun that day.

His driver had accompanied him for the first time after asking to come along on one of the General's trips, and it was he who pulled Grandaddy Bill out of the middle of a meeting as AK-47 rounds were whizzing through the trees around the compound. They piled into jeeps and sped towards the General's waiting T-39 as they watched North Vietnamese troops moving through the terrain towards the Command post. They didn't even have the door closed before they were hurtling down the runway in a hail of gunfire. "That was close, wasn't it?" Rosson reportedly said.

He was assigned Deputy Commanding General of Headquarters, US Military Assistance Command Forward on March, 1, 1968, and nine days later, the headquarters was reorganised as the Provisional Corps Vietnam, and General Rosson became Commanding General. He headed (still with his same driver) to Phu Bai where they were treated to frequent mortar and rocket fire. This was the northern part of I Corps, not far from the DMZ.

General Westmoreland had created a new "forward" command under the name Provisional Corps, Vietnam, and the previous head of the "forward" command, General Abrams, went back to Saigon. Under Prov Corps V, as it was known, Westmoreland explained that he "tailored" this assignment to fit the special requirements of I Corps, which included Vietnam's five northern provinces (including those along the DMZ) and saw some of the hardest fighting of the war.

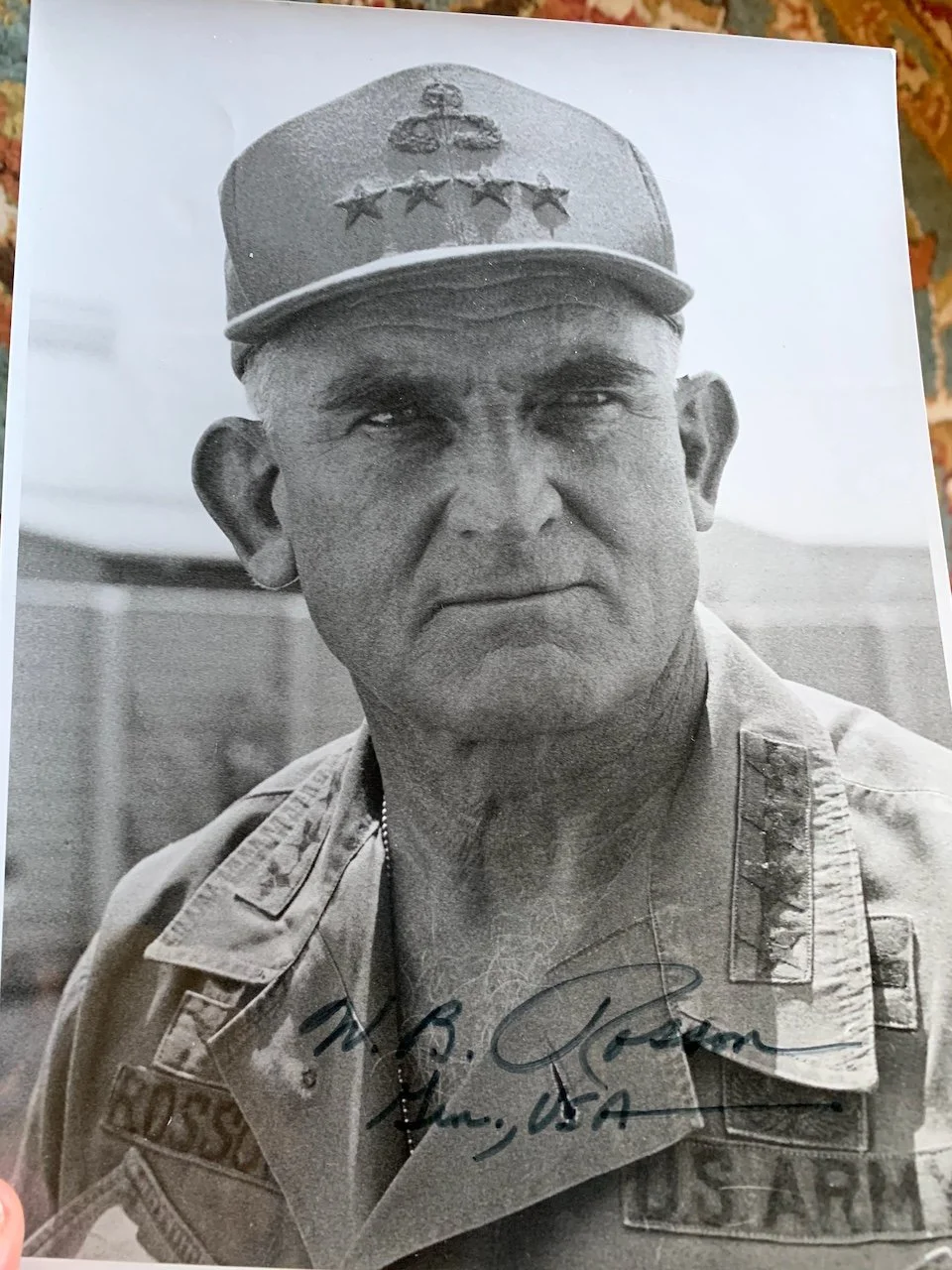

When Westmoreland was replaced by Abrams in mid 1968, General Rosson came home from Vietnam, and President Nixon promoted my Granddaddy Bill to 4-star General. He assumed duties as the Director, Plans and Policy Directorate for the Joint Chiefs of Staff. In April, 1969, he was assigned as Special Assistant to COMUSMACV, MACV GQ, Saigon, Republic of Vietnam, and a month later, he was designated Deputy Commander, USMACV, or the deputy commander of all American forces in Vietnam, working directly under Abrams.

In a time when morale was slipping and support for the war was waning, General Rosson saw to it that his men were supported. Rosson "was one of the top commanders, one of the most capable commanders in Vietnam," said Lt. General John J Tolson III, who served under Rosson as commander of the 1st Cavalry Division. "Bill was a smart soldier, in addition to knowing the art of soldiering, he had a very keen mind." Tolson continued to say he "gave his officers freedom to carry out the mission. He didn't hamstring us. He took care of us, but he saw that we got the job done. He did not come across as phony. He was a strong, charismatic soldier-leader, very apolitical. He had a terrific ethical sense. Soldiers see and understand that very quickly."

Bill Mauldin, the Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist who dubbed General Omar Bradley the "GI General" for his unpretentious manner, had a son who knew General Rosson. Lt. Colonel Bruce Mauldin, a Huey pilot and Bill Mauldin's son, said of Rosson, "Bill [Rosson] was very much the same way."

He remained in this position until he assumed command of United States Army Pacific, at Fort Shafter, Hawaii, in October 1970. In early 1973, he became Commander in Chief, United States Southern Command. His HQ was in Quarry Heights, Canal Zone. He had over a million men and women under his command. This was his last assignment before retirement from active duty, after which he immediately enrolled in Oxford University, England.

While he was studying for his Masters degree at Oxford, he occasionally traveled up to Scotland to see an Army friend who managed Balmoral Castle for Queen Elizabeth II. On one such occasion, Prince Andrew and Prince Edward, teenagers at the time, were staying at the caretaker's house. Andrew offered Bill a ride, and they all got into a Land Rover. "Andrew took off...like a bat out of hell...it was one of the most partly exhilarating, partly harrowing driving experience I've ever had." (The Roanoke Times, August 7, 1997)

In his Eulogy for Grandaddy at The Old Post Chapel in Fort Myer, VA, childhood friend General William A. Knowlton (another 4-Star in the US Army, General Knowlton passed in 2008) said that Bill "did not emerge [from Oxford] until he had a Masters Degree in International Relations. As an aside, I can imagine how much he contributed to discussions. He had lived the problems. I wonder who learned more in those classes: the student or the professor." The year was 1980.

The only transcript I have of that Eulogy was partially destroyed by flood, but in one of the paragraphs, General Knowlton began elaborating on Bill's "pixie-like sense of humor" that I found amusing, which he surmised:

"...lurked beneath a Victorian exterior...[and he] adored playing tricks, and with a totally straight face. In Paris, when word got out that one US officer was highly decorated and a bachelor, he was besieged by unmarried French ladies asking 'You are a bachelor, my Colonel?'

"To all this interest Bill developed a reply which went as follows: 'Why yes, but I never let it spoil my fun. Have I shown you the picture of my Italian daughter?' He would then produce a small picture of a 6-month old baby..."

The rest of the transcript from there is destroyed and indecipherable, but one can only guess what the rest of his story was, and similarly, the reactions from these French women.

By 1985, he was engaged to Yaya. Their meeting was one of serendipity; Grandaddy wished to express his condolences to Yaya regarding the unexpected death of her second husband, Colonel George Mitchell, in person, in a letter from Oxford. The two men were not strangers; Grandaddy had presented an award to Colonel Mitchell some years before. "I'll never hear from that man again," Yaya told a reporter she remembered thinking.

Later in his life in the mid 1990's, the Army awarded him with the Doughboy Award; the highest peacetime award for infantry. It remained hung in his house, unlike most of his other awards. The majority of his other 1,500 military decorations are on display at the National Infantry Museum, along with a uniform they wouldn't allow him to borrow to speak at an event at my high school.

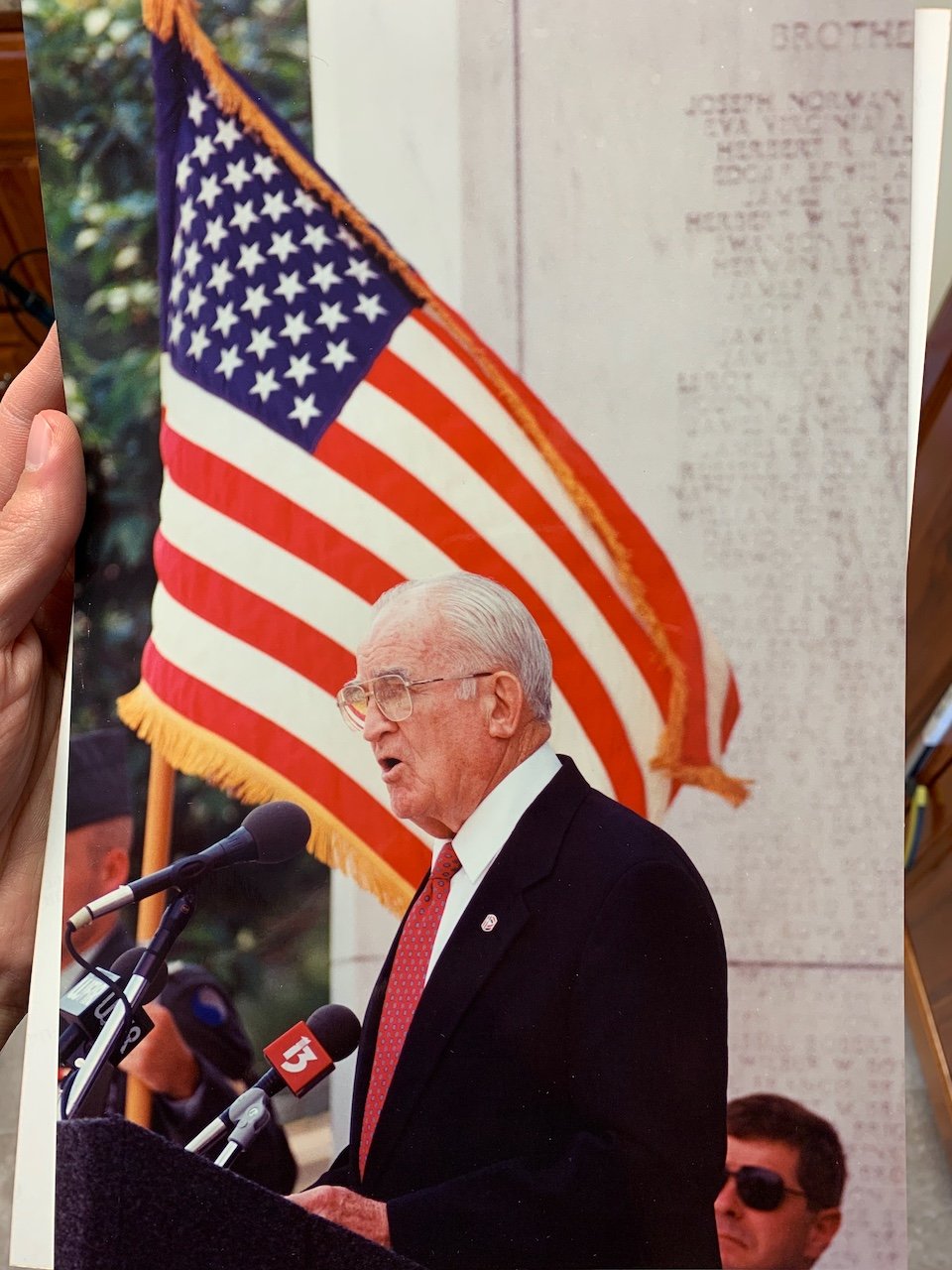

He was also instrumental in creating the National D-Day Memorial in Bedford. "He's got a deep, deep imprint on that memorial," said Mike Shelton, former mayor of Bedford. He traveled the country for speaking engagements, but never for show; always to teach.

Some of the newspaper clippings included quotes that will forever ring in my head. "Deeds speak for themselves. You don't have to embellish them." He was always thinking of others, putting them before himself when there was praise to be had, and stepping in front of them when criticism was incoming. When he disapproved of something, he did not rant and rave, but you would feel it in his icy silence. He also had a subtle, dry sense of humor, saying to a journalist, "I thought it best to donate my military memorabilia to the Infantry Museum because I had no place to store it here." The newspaper article didn't include the wry smile that probably came at the end of that statement; his house was plenty big enough to store memorabilia if he wanted. The writer did touch on it earlier in the article, saying "...the General says self-aggrandizement is not in keeping with the best traditions of the military. Besides, all of the awards he has earned store better in memory."

Yaya said to reporter John Cramer: "He never wanted anybody to call him general, but, of course, they did. He never wanted credit. He gave the credit to others." During family events, he would always say the prayer for meals, and he would always end them the same way: “Bless this food to our use and us to Thy service, and keep us ever mindful of the needs of others.”

He died in 2004. The local newspaper called him "A Four Star Gentleman." There was a state funeral (against his wishes) with full honors. "Farewell, brave soldier," General Knowlton said to close his Eulogy, his voice breaking as he looked at the casket. After the service in the Chapel, there was a horse-drawn caisson prepared outside to bring him to a plot among other officers (against his wishes).

He wanted to be buried with his men, without the fanfare. There was a heavy silence on that foggy, somber morning; it was cold and rainy, and each staccato military order seemed to hang in the mist. The polished casket was put into place on the six-horse wagon, but before the whole entourage began moving, one of the horses lifted tail and produced a large bowel movement. It brought a smile to our faces; Grandaddy would've nudged his grandchildren in our ribs and subtly pointed it out to us, no doubt wearing that wry, barely-there smile of his.

We were led by an officer on a cream-colored stallion. A 45-piece Army band marched us along playing mournful songs; I remember particularly the brass instruments sounding as vulnerable as I've ever heard, before or since. There was a color guard and a company of 130 infantrymen, bayoneted rifles on shoulders and swords swinging on the hips of the officers. The black stallion came last; riderless, there were four stars on the empty saddle. A pair of polished boots were turned backwards in the stirrups. The caisson rolled slowly to the gravesite.

We only noticed it after it had landed; but a Bald Eagle had settled on a bare branch high above, overlooking the ceremony, just before it began. The chaplain, cloaked in black with a scarlet Bible, said some words and led the Lord's Prayer. The band played, the chaplain wished Godspeed, Yaya kissed the casket and left a rose behind, and we lowered the General's body into the ground as taps rang through the vapor at Arlington National Cemetery. The Eagle watched intently. The flag was precisely folded and presented to Yaya. Nearby, 17 cannon shots boomed, shaking the ground. The smoke wafted, dissipating through the leafless trees under the leaden sky. In the murk on a different hillside, seven shadowy riflemen fired three volleys, startling us with each crack of the shots. The Eagle did not flinch. It was only after the ceremony, after nearly everyone had left, that someone looked up and noticed the Eagle had quietly flown off.

As the years have passed, I’ve come to obtain some of what was left of his things. One of those things was the flag he proudly flew at his Roanoke residence. He would raise it with the sun each morning, and lower it with nightfall, like clockwork, every day. It never saw rain, it never touched the ground. An idea began brewing in 2019 to do something meaningful with it, and with the help of some quality friends, the flag went on its own little journey.

I have no doubt he would’ve enjoyed the type of photography I enjoy. He had a sense of beauty that I believe was made all the more pronounced due to the horrific things he had seen in his lifetime. He also had an affinity for powerful machines, and their employment. I think of him often when I’m shooting military aircraft; after all, he was the first person to take me on an active military air base to watch fighter jets fly around. Oceana was one of my earliest memories of fighter jets. It was the mid 90's, and those fighter jets were F-14s. I can't recall who escorted us around, but I really wish I could remember what they talked about.

The 336th Fighter Squadron has WWII roots that predate the USAF, beginning as RAF No. 133 Squadron. No. 133 Squadron was one of three “Eagle Squadrons” consisting of American pilots before the US officially entered the war. This squadron no doubt had a hand, probably even directly once Doolittle freed them up to prowl the countryside, in helping out my grandfather as he battled his way across Europe.

I found it both appropriate and meaningful, then, to approach my friends Buck and Strap with the 336th about this project. Without hesitation for the responsibility I was asking them to take on, the answer was an emphatic yes, and the General’s flag made its way to Seymour Johnson AFB in Goldsboro, NC.

The flag made regular rides on Strike Eagles for a while when my buddy Strap’s final flight was brought to my attention. This was the culmination of my little project, and I was beyond grateful, honored, and humbled to be able to make the trip, climb the mountain, and shoot Grandaddy Bill’s flag in full afterburner with my two friends at the controls, climbing through the horizon of the mountains the General retired to.

Yaya passed recently. Some of the only things left in her room were pictures of her grandchildren and a gigantic portrait of Grandaddy. She had held on to some of the little trinkets that Bill seemed to value most; little gifts from the Far East, all stories of which must be buried in time.

I have a partition gifted to Grandaddy from General Cao - Van - Vien, Chief of the Joint General Staff of The Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces. I have a real, actual piece of the Berlin Wall. I’ve got his ribbons, his war coins, his lamp and coffee mugs adorned with Army War College or "Airborne" or the National D-Day Memorial, his gigantic portrait, a metric ton of his books…I even have a little dog (he LOVED animals) made of golf balls that Yaya made for him one year. She always liked to mention he could’ve gone pro at golf had he not been in the military.

One of her favorite stories of Bill was when he was at a fancy dinner held for the American officers somewhere in the Far East, sometime during the Vietnam era, when the delicacy being offered was a traditional soup with eyeballs in it. It was offered to the ranking American at the table who declined it, and Bill being the next in line, found it to be rude to decline it a second time, so he accepted and ate the eyeballs. He was apparently violently ill for the next few days. Yaya would always laugh when recounting that story.

There’s going to be a full-up biography written about his life; I look forward to reading it. This is just a little tribute from his grandson who’s lived another entire lifetime since his passing. Even considering his life and accomplishments, the first thing I'll remember him for is just being there for us, being our Grandaddy Bill, and to me, that's almost more impressive than his military record. Almost. Hell, he bought me my first electric guitar. It’s been enough time for me to digest who he was, and subsequently feel profound regret; I wish I had the presence of mind to ask him about his service when I was younger. To hear some of these stories firsthand. To feel the intensity of the battles, to understand what drove him… but then again, all he wanted to do was listen to me play guitar.

I hope he can still hear me, because I’ll never stop. I miss you, Grandaddy.